|

Data Acquisition Corp. DAC-512

The Data Acquisition Corp. DAC-512 "Digital Computer"

Image Courtesy Charles Falconer

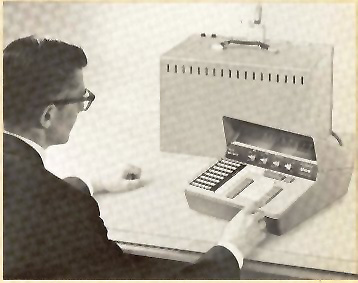

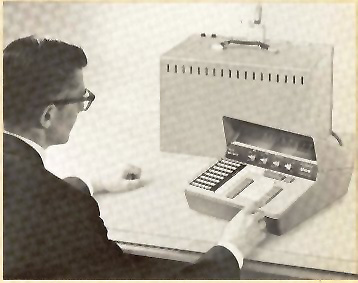

DAC-512 in use. Note electronics package containing the logic behind the keyboard unit.

Image Courtesy Charles Falconer

The Data Acquisition Corp. DAC-512 is an early

programmable desktop electronic calculator. Although the company

called the machine a "Digital Computer", it was most definitely a calculator*,

albeit a very capable programmable calculator. At the time it was introduced

(Spring of 1966), it was arguably the most powerful desktop electronic

calculating machine available, and though eclipsed historically by the

Olivetti Programma 101,

the DAC-512 remained one of the most

powerful programmable electronic calculators

available until the introduction of the Hewlett Packard 9100A in early 1968.

The DAC-512 was designed by the founder of Data Acquisisition Corp., Charles

B. Falconer (9/13/1931-6/4/2012). Falconer was born in Geneva, Switzerland

but grew up in Eastern Canada. As a youngster, he had a keen interest

in math and science. He attended McGill University in Montreal, Quebec,

where he studied physics and mathematics, with a particular interest in

nuclear physics. After college, he moved to Ontario, Canada, and took a

job at

Chalk River Nuclear, where he became deeply involved in the development

of custom hardware and computer software for

control and managment of nuclear power facilities. He became well-known

for his skills through his work at Chalk River, which resulted in Falconer

spending a lot of time traveling around the world as an expert in the field

of applying computers to the process automation for controlling nuclear power

facilities. In 1958, he moved from Canada to Boston, MA, a hub of technology

enterprise, with the intention of starting his own business

developing custom hardware and software

solutions for the nuclear power and other industries requiring precise and

fail-safe real-time process control systems. He realized his dream of starting

his own company, which he founded not long after arriving in the US.

His company was called Data Acquisition Corp., which was located

in Hamden, CT. Sometime in 1964, Falconer, having been deeply

involved with the use of expensive minicomputer systems

for data acquisition and control, believed he could design a much lower-cost

machine that could do the job. Mini computers, while powerful and fast, were

complex and could be difficult to program and use. Falconer thought that a

somewhat less-powerful, but very user-friendly machine could be a valuable

tool for data acquisition, analysis, and even process control. Falconer did

most all of design himself, and by mid-1965, a prototype of his vision

was up and running.

The prototype machine was a standlone programmable calculator, without

I/O interfacing capabilities. By the time the DAC-512 became a production

product in the spring of 1966, Falconer had developed the

I/O interfacing capabilities for the machine that allowed it to "talk" to

external equipment that could allow the DAC-512 to become the basis for

a data acquisition and control

system. At introduction, the retail price for the DAC-512 was $9,500.

This was a lot of money for a calculator, but given that a typical

mini computer system of the time outfitted for data acquisition and

process control sold for in excess of $30,000, the DAC-512 was quite a value.

The DAC-512 consists of two parts, an

operator's console that provides the user interface for the machine, including

a keyboard with keys that would light to show available operations to the

operator, a Nixie tube based display to show calculation results and

program steps, as well as other operational controls. The other

component of the system was a sizable (and heavy -- approx.

60 pound) electronics package containing the calculating logic, magnetic

core memory, and power supply.

The two units are connected by a cable that carries digital signals and power

between them.

The electronics package of the DAC-512 was built with

discrete transistorized solid-state logic (approx. 1000 transistors and 3000

diodes), and an 8192 (8K) bit magnetic core memory

(with a cycle time of 10 microseconds) which stored the working registers,

program steps, and memory registers. There were about 40 circuit boards

inside the electronics package, with each board densely packed with components.

The DAC-512 used a microcoded architecture, but not in the traditional sense of

a having a read-only memory serving as the microcode store that contains

the microinstructions that govern the operation of the machine.

Instead, the microcode of the DAC-512 was wired into specific

sections of the logic of the calculator. This

provided some functional flexibility, but required some reworking

of circuit boards in order to change the functionality of the machine,

but didn't require a complete re-design as hard-wired logic architectures

generally required.

This scheme was chosen as a reasonable compromise between cost and flexibility,

as read-only memory technolgy at the time was generally quite expensive.

The DAC-512 operated with full algebraic logic (which had only been

implemented by Mathatronics with their

Mathatron calculators up

to that time), observing the classic order of precedence of operations,

as well as allowing for overriding order of precedence using

parentheses. The machine processes the basic four math

functions, with approximate average calculating speeds quoted by Mr. Falconer

of addition/subtraction in 10mS (0.01 second), multiplication in 50mS,

and division in 70mS -- quite fast for the time. The DAC-512 utilized a binary

coded decimal floating point numeric representation with nine significant

digits and a two-digit exponent ranging from +50 to -49. The machine provided

120 memory storage registers and 512 (with this being the "512" in the name

of the machine) steps of program memory, which was

far more than anything else on the market at the time. Program memory was

divided into eight areas of 64 steps each. Each area could be used as a

standalone program or a subroutine. Eight keys at the left side of

the keyboard could cause immediate

execution of any of the eight program segments. Conditional instructions

allowed decision making within a program, and program looping for iterative

algorithms, as well as subroutine nesting capability. Every DAC-512

came with a comprehensive library of advanced math functions such as logarithms,

square roots, raising numbers to powers, statistical functions, and much more.

Due to the machine's flexible I/O architecture, an interface was developed

providing a connection a

Teletype Model 33-ASR data terminal to the calculator, providing

the ability to load and punch programs to paper tape, as well as accepting

numerical input and printing numerical output from/to the terminal.

Picker Nuclear-badged DAC-512, circa 1967.

Due to extremely competitive market conditions both in the process

automation and electronic calculator marketplace, Data Acquisition

Corp. fell victim of financial difficulties, and was purchased in 1967 by

Picker Nuclear, a division of Picker Corporation. Picker Nuclear

was a producer of electronic measurement instruments for nuclear-related

systems, and later, of medical imaging (XRay, Gamma Camera, Ultrasound)

equipment. The DAC-512 calculator was retained as a Picker Nuclear

product and was re-branded and sold under the Picker Nuclear badge.

However, with intense competition in the calculator market, it soon

became clear that the company's investment in the calculator was not going

to be profitable, and production and sales of the calculator ceased.

Total production of the DAC-512 was somewhere around 100 units.

The Old Calculator Museum is looking for any examples of the machine,

literature, or memories from anyone who may have had experience with the

DAC-512, either at Data Acquisition Corp., Picker Nuclear, or perhaps were

involved with the DAC-512 as an end-user.

If you have anything to contribute, please click the EMail button at the

top of this page to contact the curator.

* The Old Calculator Museum considers a calculator different from a

computer based the criteria that a calculator operates fundamentally on

numeric values. The manipulation of strings of alphanumeric

characters (e.g., A-Z and special characters other than + and -) is

a characteristic of a computer. Some later programmable calculators could

display or print out alphanumeric character strings, but, in general could

not accept alphanumeric strings as input, nor could they process character

strings, such as sorting, searching, or modifying character strings. There

are admittedly fuzzy boundaries to this distinction, with machines such the

Hewlett Packard 9830. The 9830

could input, output, and process character strings. However, most of this

class of machines (inclduing the 9830) would operate as a calculator by simply

entering a math expression and pressing a key to process the expression,

which would evaluate the expression and display

and/or print the answer, without any special programming.

Other machines, such as the

Wang Laboratories 700-Series, and

Tektronix Model 31,

could input and output alphanumeric character strings to

attached peripheral devices, but had very limited ability to manipulate

character strings. These machines are considered

calculators because the majority of their function centers around

performing operations on numeric values, although with their capabilities,

they certainly blur the line between calculator and computer.